Mike Martinez BS’00, MBA’11 is an unassuming CEO, the kind of person happy to make a last-minute appointment with a prying reporter on what’s actually the first day of his family vacation.

I arrive just after 8 a.m. at his office in a light industrial building in Salem. Martinez is standing near his desk in the open administrative space. Martinez serves as a trustee at Willamette and runs the twenty-five-year-old cosmetic oils producer Natural Plant Products. NPP is the manufacturing and marketing subsidiary of a business known as OMG, a cooperative of Willamette Valley grass seed farmers. Martinez is CEO of both companies.

It is a bright, sunny Monday in August. Martinez has brewed a pot of coffee and offers me a cup, along with half-and-half from a half-gallon carton. I take him up on both. Once the coffee is situated securely in travel mugs, we decide to go take a look at the manufacturing area.

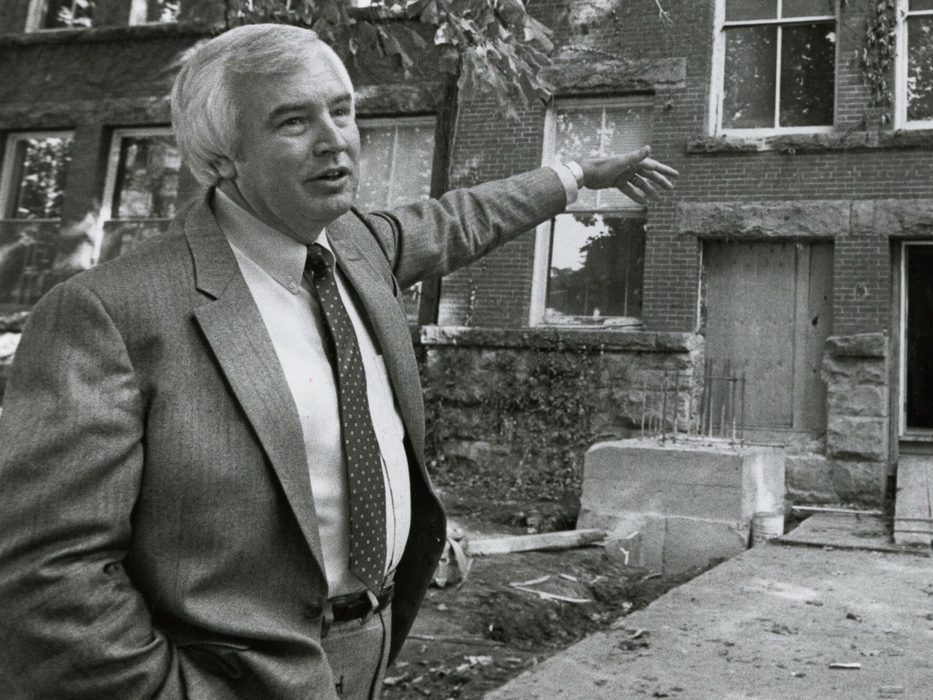

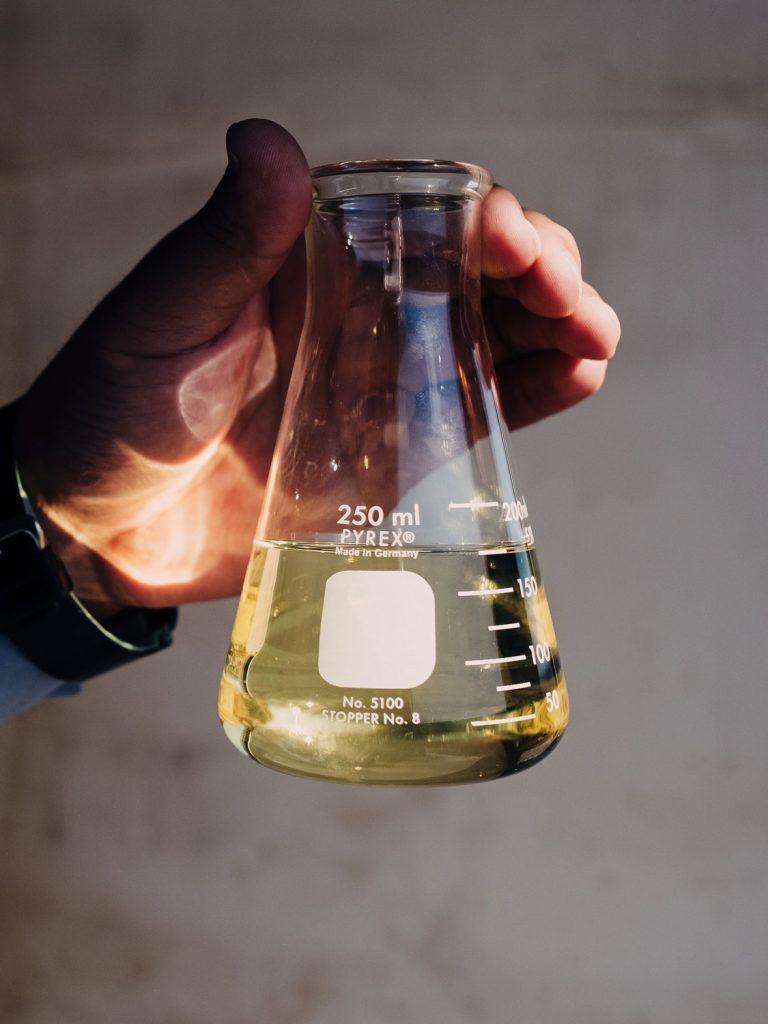

↖ Three views of the manufacturing area. The Salem plant processes meadowfoam seeds into oil that is used in cosmetics. The oil is prized for absorbing quickly and not feeling greasy when applied to skin and hair.

NPP occupies 15,000 square feet within Mill Creek Corporate Center. The company’s section of the complex, on this morning at least, is quiet, and is dwarfed by neighbors a mile to the north like Home Depot and FedEx, whose warehouse footprints take up ten to twenty acres. More recently, Amazon opened a million-square-foot warehouse with enough bays to load ninety semis at once.

The irony of twenty-acre buildings cropping up around the Willamette Valley—renowned worldwide for its rich soils and optimal agricultural conditions—isn’t what brings me here today. Nor is the juxtaposition of an agriculture-dependent producer of niche beauty oil existing in the shadow of global retail giants.

So I follow Martinez’s lead and put on a fluorescent yellow safety vest.

He tells me NPP recently moved into this space and that it’s not merely a relocation. “This marks a new chapter for us: It means we have our own milling and production. With it we can process seventeen tons a day,” Martinez says. That volume aligns with daily demand and allows NPP to flex according to anticipated need.

“We sacrifice some efficiency and pay a bit more to process,” Martinez says, “but we have ownership over the successes and failures that come with manufacturing.”

OMG and NPP’s story dates to the 1980s, when seven farms whose primary crop was grass seed decided to collaborate on growing another crop—meadowfoam—for rotation. At the time, Willamette Valley grass seed farmers relied on field burning for pest control. Following harvest every summer they burned roughly 250,000 acres. Air pollution from those burns often became overwhelming. State lawmakers felt pressure to address the problem, and by the early 1990s, they had introduced a policy to phase out the practice.

Which brings us to the appeal of meadowfoam. This low-growing flower, whose scientific name is Limnanthes alba, was first classified in 1833. It earned its name because its tiny white flowers resemble the froth of ocean waves. As the co-op farmers discovered, it not only rejuvenates grass seed acreage without burning but also bears seeds rich with oil. This oil happens to have unique chemistry for rapid absorption when applied to skin and hair, without feeling greasy.

↑ “We sacrifice some efficiency and pay a bit more to process, but we have ownership over the successes and failures that come with manufacturing,” says Martinez of the move to in-house milling and production.

___

The co-op spent years researching and hybridizing the plant for varieties to cultivate commercially. By 1997, the cooperative grew to more than eighty farmers. They formed NPP that year with the hope of creating a commercial market for the oil.

A few years later, Martinez was hired fresh out of Willamette with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. He would be their first marketing director, joining the CEO as one of two employees. “When I started college, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, other than I knew I wanted to do something in science,” he says. When he landed in his job, the organizations were struggling to overcome a debtload of $10 million, surplus inventory, and a limited customer base.

Since then, NPP has gone from having piles of debt and unsold seed to generating annual revenue of $10 million. Martinez became CEO in 2010. Today, the company’s oil is an ingredient in products such as Dior Prestige Le Micro-Caviar de Rose, Laura Mercier Nourishing Rose Oil, and Aveda color balm. The company has eleven employees, and Martinez anticipates adding another twelve once manufacturing moves fully in-house. OMG has fifty-three members farming meadowfoam on 10,000 acres throughout the valley.

Stepping onto the production floor, still sipping coffee, I notice humming. It’s coming from equipment. Nearby, an NPP worker on a forklift feeds meadowfoam seeds into a hopper leading to an oil press. A contractor assesses how to make gates for chutes connected to storage tanks for seeds.

Critical pieces of equipment are on the way, including a distiller being built in the Czech Republic. Martinez says he hopes to have the machinery fully functional and all manufacturing happening on location by spring.

Martinez shows me the machine that extracts the oil. Dark, particulate-laden crude drains profusely from half a dozen openings into a channel feeding a 155-gallon vat. Cake left over from the pressing falls into a chute dropping to a 1,500-pound polybag. That cake is sold as fertilizer.

↗ The market for meadowfoam oil is more reliable than that for grass seed, Martinez says. He estimates that revenue from the oil amounts to 5 to 10 percent of revenue for each member farm.

If you didn’t know the history of grass seed farming in Oregon or how every year the state loses an average of 85,000 acres of farmland to other uses, it might be difficult to appreciate what’s actually happening here: NPP is helping to keep Oregon agriculture alive.

“The market for meadowfoam is more reliable than grass seed markets. This contributes to the sustainability of many multi-generational family farms,” Martinez says. He estimates revenue from meadowfoam amounts to

5 to 10 percent of revenue for each member farm.

After we see the plant floor, we walk back to the office and take seats at a table in front of a sunny window.

It’s almost 10 a.m. Martinez pours more coffee, and we start talking about travel. This leads to a conversation about his family roots—his grandfather’s family migrated from Chihuahua, Mexico, to New Mexico. Martinez tells me his grandfather was born in Gallup, New Mexico, and that his father was born in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. His mom was born a stone’s throw away from there, in Santa Fe Springs, California. Martinez himself grew up near the beach on the outskirts of Long Beach. Today, his favorite travels are to New Mexico.

I see it’s almost 10:15: it’s taken me more than 120 minutes to finish my coffee. So I put away my pad and pen, bid Martinez goodbye, and head to my car. He’ll be catching a plane to Southern California in the afternoon.

As I drive back up the valley toward home, I see grass seed farms bordering the freeway. This section of I-5 hasn’t changed much in the five-plus decades I’ve been traveling it. And I’m thankful for Limnanthes alba and the part it’s playing in maintaining a bit of the Oregon I know.

••

Shelly Strom is a freelance writer who previously covered agriculture for Portland Business Journal as a staff writer. She grew up in Oregon, where she spent summers picking berries and later worked the sorting line of a fruit processor, and now splits her time between Vancouver, Washington, and Port Townsend, Washington.