For years, I’ve kept the same photo as my computer desktop background, one that represents what might be the most pivotal moment of my daughters’ lives. It shows my oldest child as a toddler, a few days shy of three years old. She’s in a hospital room, wearing a gold- striped shirt and a pair of tights patterned in pink bows. In the excitement, pants have been forgotten.

In the photo, she’s peering into one of those translucent maternity-ward cribs at a swaddled little breadloaf of a newborn. For the first time, she is laying eyes on the person who will accompany her on more of life’s road than anyone else: her sister.

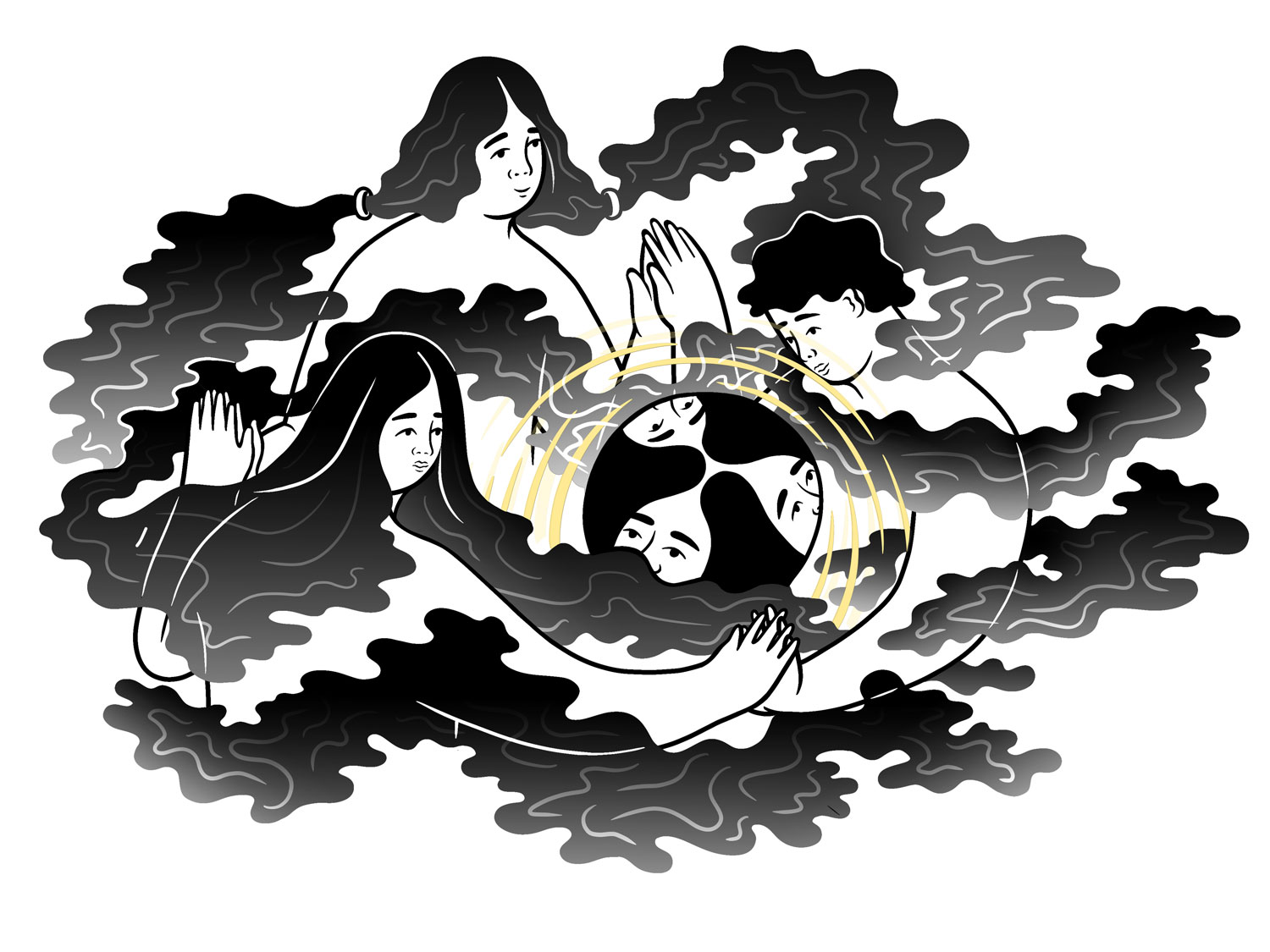

Siblings are standard in the United States, if not universal. Researchers say about 80 percent of all Americans have at least one brother or sister. A growing body of research shows that siblinghood is among the most powerful human bonds we experience: our sisters and brothers have the potential to be the longest, most enduring family relationships of our lives.

I wouldn’t know. I’m an only child, the sole product of a union between two aging former hippies edging their way into the 1980s. I can’t say I wished much for a sibling as a child. To me, my parents, my goldfish, my dog, and an unending stack of books sufficed nicely.

Until I had children of my own, siblinghood was something I observed from an anthropological distance. In the hours I spent at friends’ homes as a child, I took mental notes of sibling scenarios. There was the morose, door-slamming teenage brother who wore his hair like a curtain across his face, appearing only briefly to microwave pepperoni pizza Hot Pockets before retreating to his room to blast TOOL. There was the wild-card little sister who ended up in the emergency room for sticking a bit of umeboshi (pickled plum) too far up her nose. Once, I sat aghast as that same sister admitted to using her sibling’s toothbrush on purpose for months.

“I thought you wanted me to,” she shrugged.

My life as an only child was not this exciting.

I still don’t believe I had a lesser childhood, or that not having a sibling warped me particularly. (My husband might beg to differ.) As I became an adult, though, I began to see the full value of siblings. Brothers and sisters are shared historians, keepers of memories. Siblings confer a sense of rootedness in the world. “You’ve been my sea wall,” is how the writer Mary Karr describes it.

So when I contemplated motherhood, I knew that I wanted any child I brought into this world to have a sibling. We had two daughters—the girls whose meeting is documented in that photo on my computer. And just when I thought my childbearing career was over, kismet delivered us a baby boy. And that is how an only child ended up the mother of three.

Now, every day, I watch the mysteries of brother and sister relationships play out in my own home, a minute-to-minute cycle of simultaneous love and strife, alliances and grievances constantly shifting. A reneged upon promise to play yet another game about dinosaurs with a little brother. A morning squall over socks, or oatmeal, or a borrowed hair scrunchie. But I also see them shape each other’s lives and personalities in subtle and profound ways.

One thing I had never understood as an only child is just how much new ground siblings take on. There is always a sibling who is the first: to get their ears pierced, learn to read, ride a bike to a friend’s house alone, go away to camp. I realized this when the sisters made a plan to meet up on the elementary school playground, so the older could give the younger, then a new kindergartener, a tour, imparting arcane knowledge about monkey bars and specific hills where specific sets of third graders liked to hang out. Or when the middle sister taught her little brother to pedal a bike, putting him through a rigorous set of driveway drills with the dedication of a high school football coach. I hadn’t known how much of the world is first encountered through the experiences of brothers and sisters, the extent to which a sibling—not a parent—is a first, best guide.

I am no expert in sisters and brothers, and I know it. But as a close observer with a vested interest, one thing is clear: The most certain poison to sibling relationships is competition. I try, in a surely imperfect manner, to avoid comparing my children. I probably fail in a hundred other ways, fodder for future therapists to unpack.

It’s a comfort, though, that my three children are together in this world. In my closely held hopes, they are adults who find not just comfort in their shared past, but the kind of friendship that’s only possible with someone who has known you since birth.

When I tiptoe into the sisters’ shared room at midnight the reading lamp is still on, but the room is quiet except for the sweet rhythm of breathing. I always find them curled asleep together in the bottom bunk, the occupants of a small, sovereign land of their own, to which I have no map.

••

Michelle Theriault Boots BA’05 is a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News. Her work has won local, regional, and national awards, including a 2021 National Magazine Award for community journalism. She was a 2017 Kiplinger fellow in public affairs journalism and a 2020 Harry Frank Guggenheim criminal justice reporting fellow. She and her husband, Kevin Boots BA’05, live in Anchorage, Alaska, with their three children and an elderly golden retriever.