I

It’s often said that friendship is never an accident. Bonnie Hull and Ellen Crocket began their friendship three decades ago, while working together at a café near Willamette.

For many Willamette alumni, Hull is nearly as well-known as her husband, the beloved late art history professor Roger Hull. She owned the café with another friend, and Crocket worked there, helping out during the early, intense days of its launch. But then Crocket’s marriage ended. She left behind her in-real-life friendships in Oregon, decamping first to a family cabin in Maine for a winter of healing, and eventually to Vermont, with stops over the years to care for grandchildren in Wyoming.

Despite the distance, Hull and Crocket remained in touch. That first lonely winter, Crocket spent as many as three hours a day writing letters to friends and family, including Hull, from a typewriter at the cabin. It was the beginning of their ink-on-paper connection, as well as a glimpse at how their future correspondence would unfold.

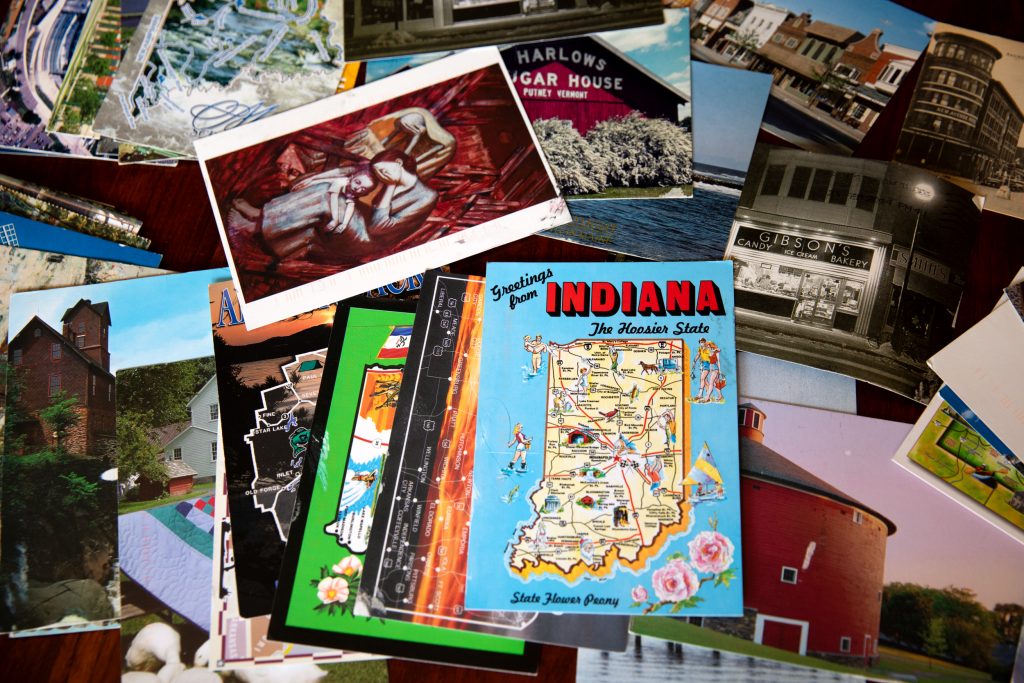

Their friendship drew others into its orbit. The Hulls visited Crocket on the East Coast. Crocket remarried, and she and her husband, Larry, visited the Hulls, too. They traveled cross-country from Vermont by car, stopping to see friends and family along the way to Oregon. Crocket often purchased postcards on their cross-country journeys, but she didn’t always send them.

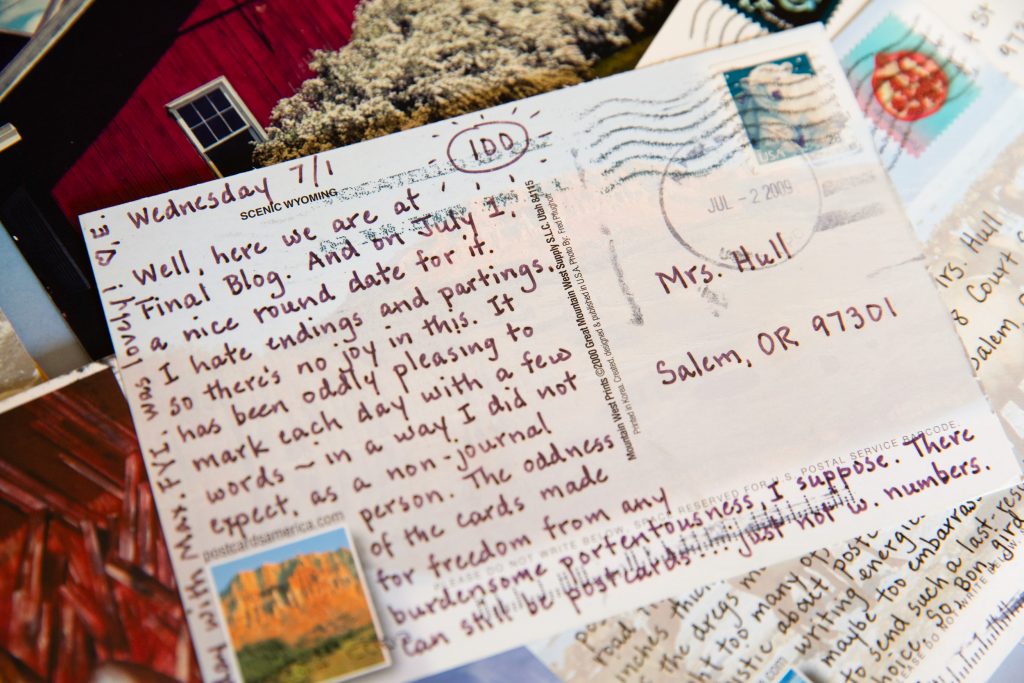

Then, in 2009, Hull began blogging about her daily life as an artist in Salem and her travels with Roger. At the time, Crocket had limited access to high-speed internet at the cabin in rural Vermont where she lived with Larry, a retired pastor she met at a singing camp. Her analog response to Hull was “the Snail Blog,” handwritten dispatches on those old postcards. Her notes depicted a very different life from that in Salem, a small-town New England life marked by church potlucks and choir practice.

Crocket pledged to send 100 cards from her stash, writing: Lucky you. I’m actually going to do this: send you every one of the stockpiled postcards left over from all those road trips. … Bon, gird your loins for the Snail Blog.

S

So began the first of thousands of daily postcards from Vermont to Salem. This analog response to Hull’s chatty blog continues sixteen years later, the connection between these two women deepened by the daily commitment of a New Englander who found her voice as a writer and an Oregonian eager to receive what she viewed as an art project of a lifetime.

“It didn’t take too long for me to realize that this was something remarkable,” Hull says.

When Crocket hit her 100-postcard goal, on July 1, 2009, she understood that she didn’t want to stop. The daily practice had become a ritual for her, as well as for Hull, the recipient. It has been oddly pleasing to mark each day in a few words, in a way I did not expect, Crocket wrote on the 100th postcard. Crocket had never seen herself as a writer, not until the postcard project. She didn’t even keep a journal.

“I never was able to do that, because I always got stuck with the question of, ‘Who is this for? Who’s the audience?’ And that had implications as far as, ‘What do you need to explain? Is it really just yourself that you’re writing to, or is it posterity? Is somebody going to read this someday?’” Crocket says. “So that kind of got in my way, but writing everything on a postcard and sending it to Bonnie didn’t have that problem. I was writing it to her, and I knew when I needed to explain who someone was and when I didn’t.”

“It didn’t take too long for me to realize that this was something remarkable,” Hull says of the letters. She calls them “a brilliant record of a life.”

↑ A phone photo of Bonnie Hull (left) and Ellen Crocket Willamette vice president Shelby Radcliffe when the trio gathered in Vermont this fall. In anticipation of the trip, Radcliffe wrote her own postcards to Crocket.

From the start, Hull delighted in Crocket’s turns of phrase. A nightgown day, for example, is “when she can sit and read all day,” Hull says. “And those are few and far between.”

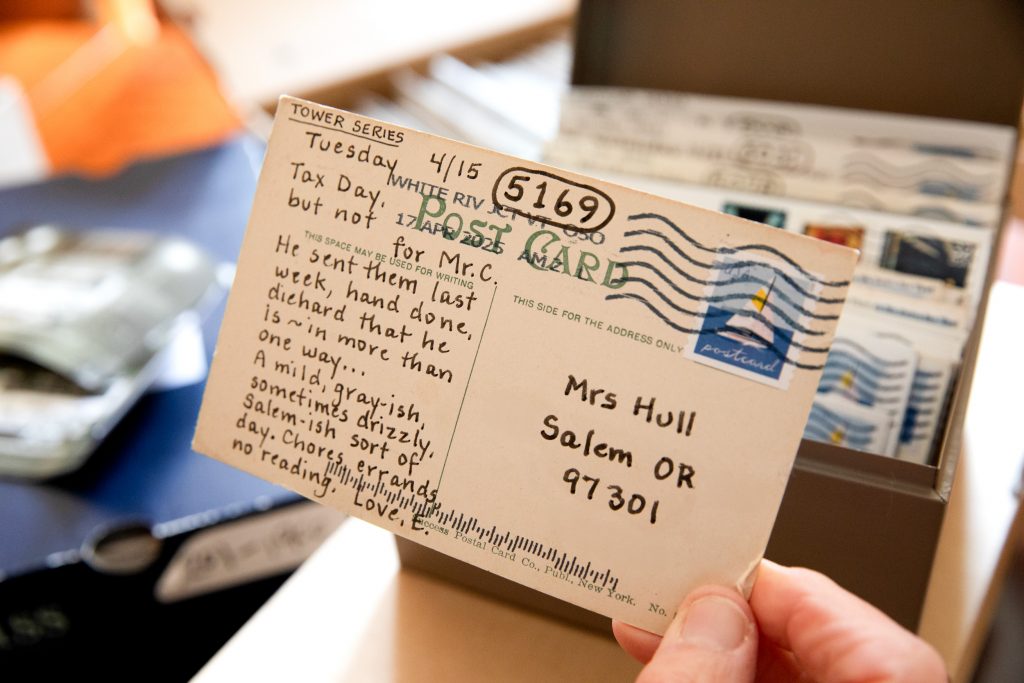

Then there’s Postcard No. 894, written during what Crocket describes as a day without walls, her description of open-ended hours that bring no obligations outside of the home. She wrote about how the sky was gray, not unlike Salem in winter. We did rustic things: stacking the last cord of wood (thereby evicting a family of voles) and canning the apple butter I’d been cooking down off and on since Tuesday.

Postcard No. 5,074 is a recently arrived dispatch that Hull read aloud during our phone interview: A slow morning got speeded up in order to get to the dump. Very necessary before closing time. Lots of other people came at this deadline moment. Too little reading, too many chores. “If you’re doing it regularly, like Ellen does, you can tell an awful lot in three sentences,” Hull says. “They’re typically not much more than three sentences, but a feeling is conveyed. You get the sadness or the joy.”

A

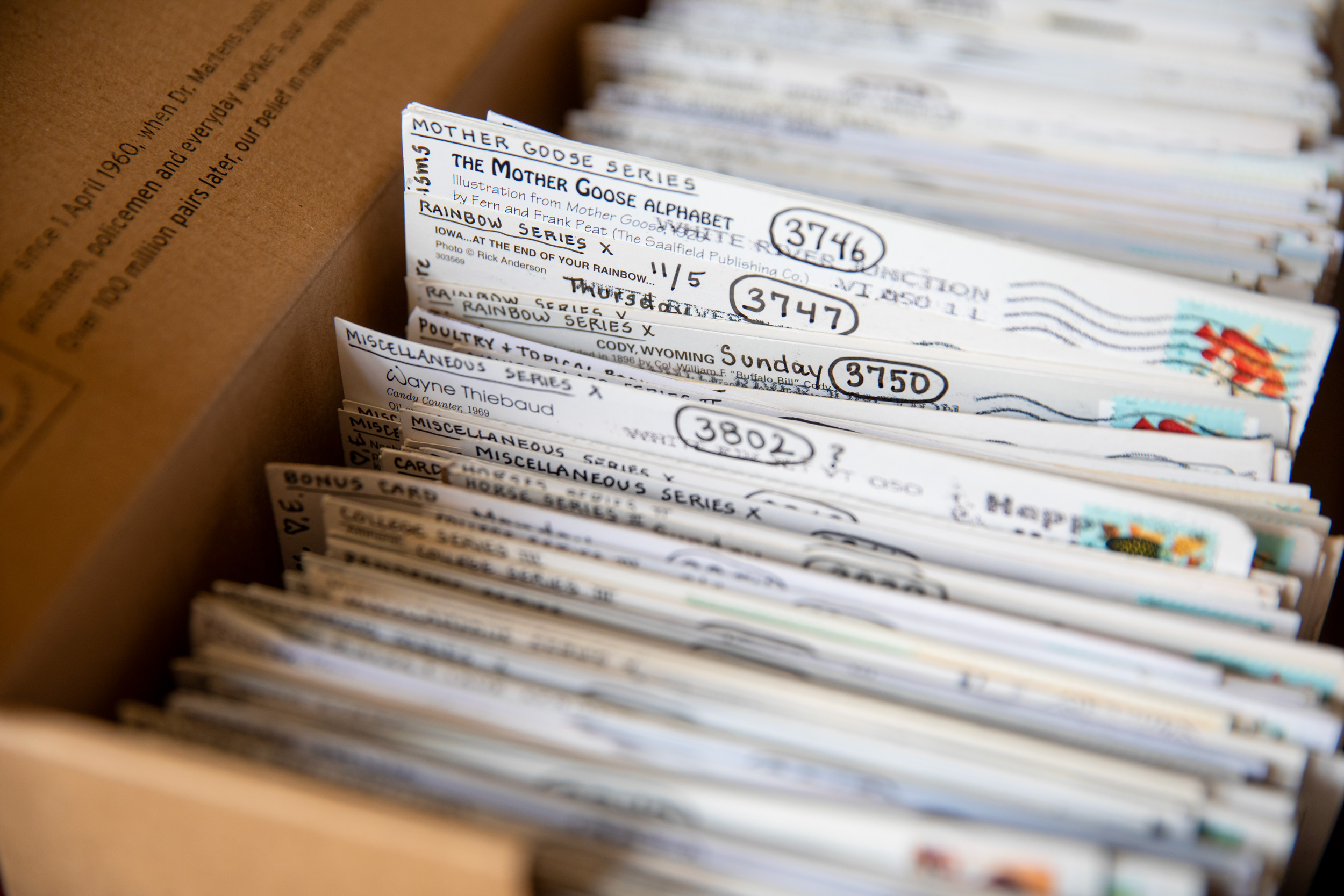

As the years passed, the circle of friendship grew to include Shelby Radcliffe, Willamette’s vice president of advancement. While visiting Roger Hull before his death in 2023, Radcliffe caught a glimpse of a stack of cards from Crocket. Like his wife, Roger read the postcards daily. Bonnie Hull invited Radcliffe to look at the cards, too, stored chronologically in shoeboxes.

As Radcliffe thumbed through the contents of the boxes, she got hooked on the story of Crocket’s life in Vermont and wanted to meet her. She persuaded Hull that they should travel together to Vermont to visit Crocket in person. In preparation for the trip, Radcliffe began writing daily postcards of her own to Crocket in Vermont. Radcliffe and Crocket formed their own friendship via handwritten note. And Radcliffe ended up the subject of more than a few of Crocket’s cards to Hull.

I got number 34 from Shelby today. I’m really starting to like her, Crocket wrote.

“I was hopeful that they would hit it off,” Hull tells me. “I kind of knew they would.”

Hull and Radcliffe flew to Vermont in fall 2024. The trip offered Radcliffe a glimpse of Crocket’s small-town life—not to mention a taste for Vermont’s signature frozen treat, the maple creemee.

“She was very warm and very open, as if we had known each other for a while, and that was surprising, because I’m this person who’s just shoving myself into her life,” Radcliffe says. “She was quite funny and candid”—exactly as Crocket had come across to Radcliffe in Hull’s collection of postcards.

Consider the wry observation of Postcard No. 785, from 2012: All films narrated by Morgan Freeman are stirring, are they not? Or a postcard written during holiday bazaar season, a time of year that keeps Crocket busy as one of her town’s chief cookie bakers: What would Jesus do? Well, this is usually a rather imponderable question, but I do think we can be certain of one thing. He would not hold a Christmas bazaar.

This summer, Hull and Radcliffe plan to assemble a selection of Crocket’s postcards for an exhibit at Bush Barn Art Center in Salem.

“I’m kind of an archivist at heart,” Hull says. “At one point I offered to give them all back because I felt it was such a brilliant record of a life, a life very different from my own life. And she said, ‘No,’ that, for her, it ends when she puts it in the mail slots. She didn’t want them back. So I just kept keeping them.”

“I’ve assured her that I do not want them,” Crocket confirms. “If she sends them to me, I’ll have a large bonfire.”

↑ Hull keeps the postcards in shoeboxes, organized by date. “They’re typically not much more than three sentences,” Hull says, but “if you’re doing it regularly, like Ellen does, you can tell an awful lot in three sentences.”

F

For Crocket, the writing ritual begins when she selects the day’s postcard. Fewer places sell postcards now, so she often relies on friends with their own unused cards. Crocket organizes the cards by image theme: Couples, Boston Series, Barn Series, National Parks, Fishing Series. She keeps the cards stacked by theme in a tin on her dining room table.

Radcliffe is especially charmed by the whimsy of Crocket’s “poultry bonus cards.” This is the poultry-themed stash that Crocket dips into when she can’t fit all of her news on one card, to accommodate the overflow. There are lupine bonus cards, too, because Crocket has collected (or been given) an outsized number of cards depicting these purple flowers.

Crocket has a signature writing implement—the Sakura Pigma Micron Pen, which she adopted while working in an architecture office in Wyoming—as well as signature penmanship: precise block lettering. “I usually write the address and put the stamp on it,” she says, “and then I think, Well, what will I say?”

Despite the daily ritual, Crocket doesn’t view herself as disciplined. “Most of my life, every day happens the way it happens. I don’t have a schedule in mind or anything like that. So I think when this came into my life, it was different from anything else I did, in that I was pretty much committed to doing it every day.”

The correspondence may seem lopsided, but Hull often responds via long emails. They also communicate via text message, including sharing their New York Times Spelling Bee scores. Still, like all good friends and committed correspondents, Hull sometimes knows more about Crocket than her friend knows about her—and vice versa.

For Hull, receiving the cards and organizing them for exhibit has been a solace in the time after her husband’s death. And for Crocket, who has become a caretaker for her own husband, who has Parkinson’s disease, the cards she writes serve as a welcome distraction from the burdens of caretaking.

Send Your Own Postcard

Pick a card and a pen and compose a note to a friend who lives far away. Unsure

what to write? Annette Hulbert, director of Willamette’s Writing Center, offers these three tips:

↓

1. Give a general sense of your location. Athough you don’t need to disclose specifics (a postcard is, after all, a public form of writing), it is always appropriate to open your brief letter with the formula “Greetings from ______.” Regardless of whether you are writing from Spain or from campus, the context will be appreciated.

2. Include a specific detail. What can you

see from where you are writing? Give your reader

a tidbit from your life.

3. Consider your reader.

Space is extremely limited on a postcard, but adding in a question might inspire your reader to write back. Jane Austen frequently opened her letters with inquiries and ended by imploring a response: “I shall be extremely impatient to hear from you.”

“We have come to believe that as long as she has a stack of cards to write, and I am reading them, we will stay alive,” Hull wrote on her blog in 2015, an electronic response to Crocket’s 2,000th postcard. In that milestone postcard, Crocket had written that she couldn’t have imagined how deeply woven into the cloth of my daily life this little writing project would become. She joked about how it guaranteed them life everlasting.

The connections we make are really all we have. That’s all that’s left of us at the end of it all.

This sentiment became more poignant as 2,000 cards turned into 3,000 and then 4,000 and then 5,000.

“I count on them now,” Hull says. “I want to know what she’s doing every day.”

Our deepest friendships are often formed in our youth, when we have what seems like endless time. Or they emerge at times of crisis, intensity, or midlife transition, when we’re most receptive to welcoming new people into our lives, as Hull and Crocket were thirty years ago. If we’re lucky, our friendships deepen as we share experiences over time. But it’s not always easy to remain connected. To sustain a daily correspondence across time and distance is a rare act of holding another human in one’s heart. It requires commitment and care.

Every day, Hull is thinking about Crocket. Every day, Crocket is thinking about Hull.

“I can say perfectly honestly to Bonnie: ‘I think of you every day,’” says Crocket. “And how else would you be able to say that to somebody for twenty years, that you honestly think of them every single day? But I do, and that’s something very precious to me.”

“It isn’t just sentiment,” Hull says. “Although each in our own way has sentimental feelings about the other and about the lives we’ve lived, that’s not what this is about. It’s about something else: The connections we make are really all we have. That’s all that’s left of us at the end of it all.”

••

Erika Bolstad is a Portland-based journalist and the author of the memoir Windfall, which was a finalist for a 2024 Oregon Book Award.