Forty years ago, I began my graduate studies at the University of North Carolina with the goal of studying, writing, and engaging in church-state matters. I grew up in a religious household with several relatives who were clergy (including my father). I was inclined toward politics and law rather than to the ministry, and to focus on church-state matters as a scholar and lawyer seemed like a natural fit.

Since then, I have never looked back. My wife reminds me how fortunate I am in having found a niche that has inspired and sustained me for so many years. That is due in no small part to the seemingly intractable controversies surrounding church and state interactions in the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, 55 percent of Americans support the idea of church-state separation, with only 14 percent opposing it. (The remainder hold mixed views.) An even higher number—69 percent—agree that the government should never declare an official religion. At the same time, more than half of Americans believe (to one degree or another) that this is a “Christian nation” and that the founding documents and/or founders were inspired by biblical principles.

This tension plays itself out on an almost daily basis in the trenches of America’s cultural wars. Even though the U.S. Supreme Court declared some seventy-five years ago that the government should not fund religious instruction, and more than sixty years ago that public schools should not promote religious activities, both issues remain contentious and serve as fuel for partisan legislation. So the Louisiana legislature has required the posting of the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom; the Texas legislature has authorized public school chaplains; and the Supreme Court has split 4–4 on whether Oklahoma can fund a Catholic-run charter school. And as our nation’s commitment to diversity and equality has grown, an increasing number of religiously affiliated entities that serve the public—hospitals, nursing homes, etc.—and businesses owned by religious conservatives—for example, Masterpiece Cakeshop—are claiming religious exemptions from nondiscrimination and other salutary regulations.

Fueling these immediate controversies is the above- mentioned philosophical divide: should America’s public institutions and policies reflect (and support) religious values, and if so, which ones? This implicates the question of whether the long-held idea of separation of church and state is the correct model to follow. Despite its general support, it has become increasingly controversial, with Justice Clarence Thomas calling it a “so-called” constitutional principle.

In 2022, Cornell University Press published my sixth book, Separating Church and State: A History, in which I examined the historical impulses for the idea of church-state separation. Those include Enlightenment thought, Radical Whig political theories, and dissenting Protestant traditions. These impulses informed our nation’s founding documents and directed later relationships in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. I arrived at the conclusion that the bona fides of church-state separation are significant, notwithstanding current criticism.

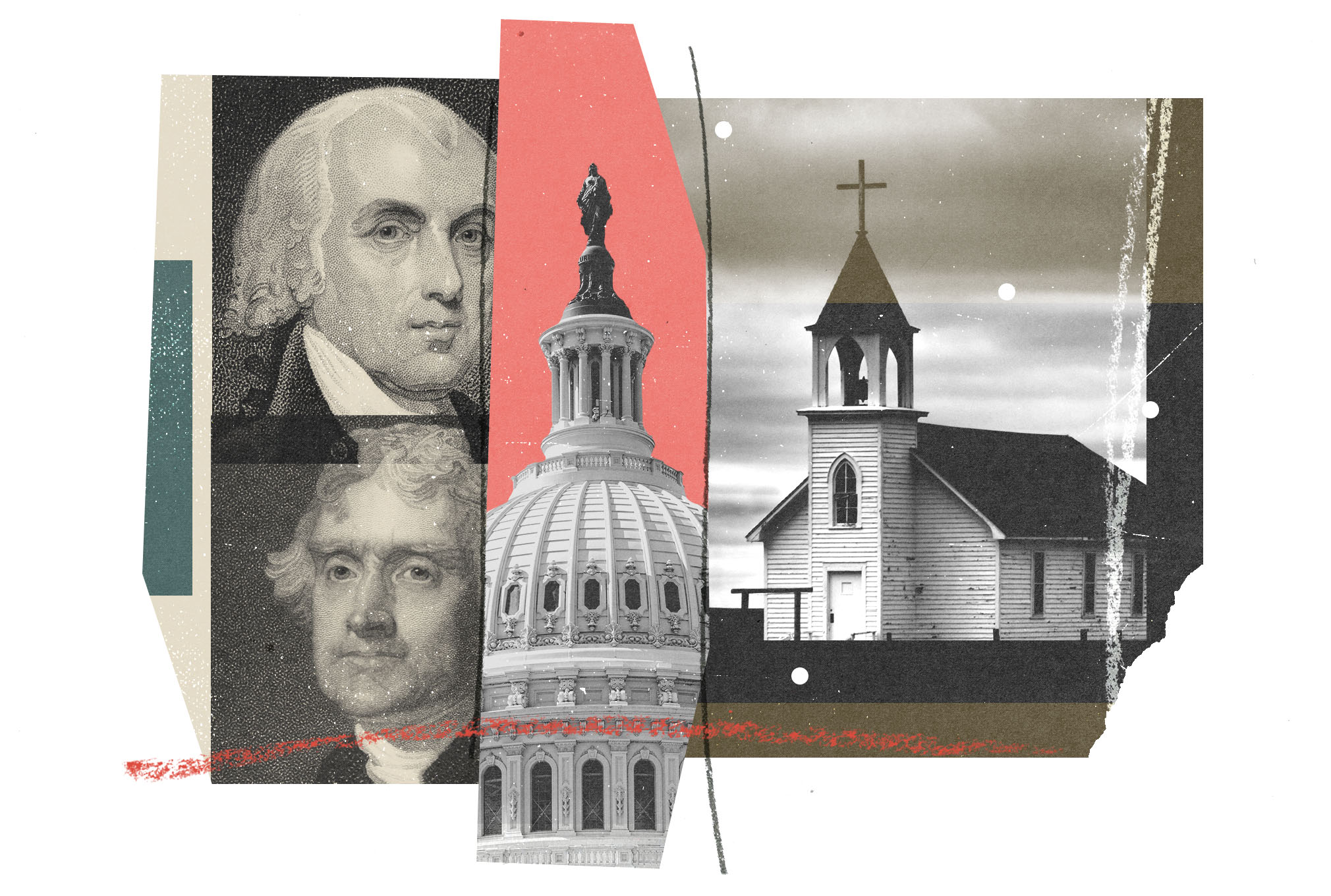

That book led me to undertake my most recent book, The Grand Collaboration: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and the Invention of American Religious Freedom (University of Virginia Press, 2024). For decades, historians and jurists have considered Jefferson and Madison to be at the forefront of the nation’s development of religious freedom. Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom and popularized the phrase, “a wall of separation between church and state.” Madison was instrumental in writing the First Amendment, which contains the Free Exercise and no-Establishment clauses.

More recently, critics of church-state separation have sought to minimize Jefferson’s and Madison’s impact. Their criticism takes two tracks. The first is that the two men were largely outliers when it came to contemporary attitudes about church-state relations—that they were unrepresentative of the founding generation. The second argument, somewhat at tension with the first, is that neither man was as separationist as he has traditionally been depicted.

In writing The Grand Collab-oration, however, I sought to avoid engaging in the current legal debate. Rather, the book addresses several questions: What experiences influenced Jefferson and Madison to embrace religious freedom as a central cause, particularly when they faced so many pressing issues related to creating a new government? Why would two religiously heterodox and nominally observant men, immune from any threat of religious persecution thanks to their social standing and putative affiliation with the dominant Anglican Church, possess such a deep commitment to religious freedom and work so assiduously throughout their lives to advance that principle? Finally, what were their understandings of the concept of religious freedom, and what other values did that concept reinforce?

To find answers, I examined many of the 2,300 letters between the two men contained in various collections and compiled on the National Archives website Founders Online. I also looked at correspondence between each man and other acquaintances (such as John Adams and James Monroe) that discussed how religion should interact with government policy.

My conclusion is that Jefferson’s and Madison’s support for religious freedom was tied to its connection to freedom of inquiry and conscience. “Reason and free enquiry are the only effectual agents against error,” Jefferson wrote in his Notes on the State of Virginia. Similarly, Madison declared “the freedom of conscience to be a natural and absolute right,” not one granted by governments, and a healthy separation of church and state was key to ensuring freedom of inquiry and conscience.

As the current Supreme Court continues to rewrite church-state law, it should not ignore the legacy of the two founders, who did more to secure America’s much-envied regime of religious freedom than any other figures. As Justice Sandra Day O’Connor observed in her final opinion concerning the Religion Clauses: “Those who would renegotiate the boundaries between church and state must therefore answer a difficult question: Why would we trade a system that has served us so well for one that has served others so poorly?”

••

Steven K. Green is the Fred H. Paulus Professor of Law and Affiliated Professor of History and Religious Studies at Willamette.