I

In 2021, Alyssa Eklund BA’21 set up wildlife cameras at Lookout Creek in the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, an Oregon State University research site fifty miles east of Eugene. Eklund was studying interactions between wildlife and large wood—deadfall complexes of logs, sticks, and debris, or sometimes a single fallen tree. Her footage revealed activity from bushy-tailed woodrats, great blue herons, black bears, and dozens of other species. Some animals used logs as bridges, while others, like belted kingfishers, used them as perches, diving into the water to catch prey, then returning to the log to eat. An especially stunning video shows a mountain lion springing several feet from a mossy boulder onto a suspended log.

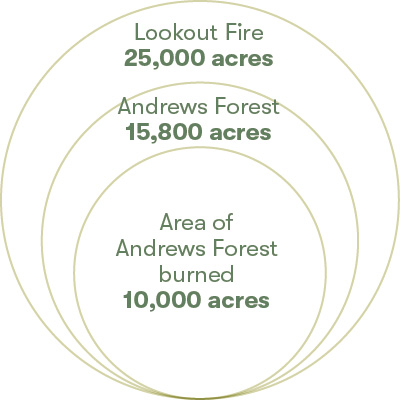

As Eklund and I spoke last summer, she informed me that the Andrews Forest was actively burning in the Lookout Fire. By late September 2023, more than 25,000 acres total had burned, including about 10,000 of the experimental forest—sixty-five percent of the forest. It is one of dozens of massive wildfires that have burned US forests in the past twenty years.

Megafires, as they’re known, are defined by the burn area’s acreage; while there’s no consensus on the size that constitutes a megafire, one study defines them as any fire greater than 25,000 acres. In addition to drought, high temperatures, and extreme weather intensified by climate change, US government policies from a century ago have exacerbated the proliferation and frequency of megafires.

Forest management practices are adapting to a warming climate that threatens US forests. The issue is complex—until recently, little consensus existed on responsible management. In previous years, environmentalists often advocated for the preservation of old-growth trees and the animals that depend on them, like the northern spotted owl, by leaving the forests alone to self-regulate. Meanwhile, the US Forest Service sold lumber contracts to private companies that clear-cut large swathes of old-growth.

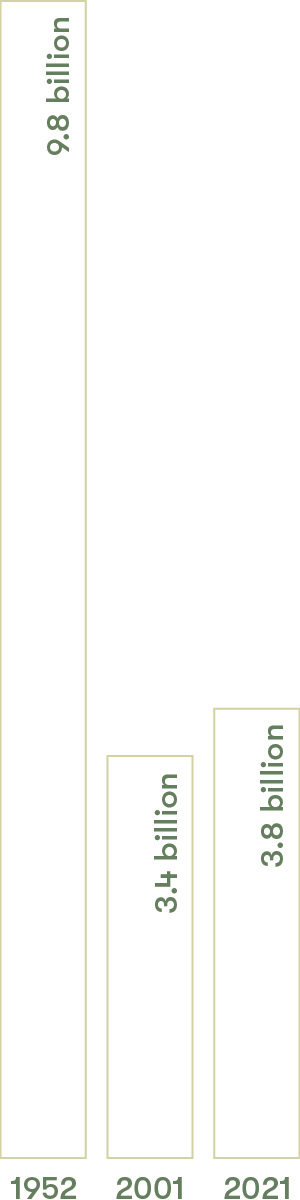

For decades, the Willamette National Forest yielded more lumber than anywhere else in the country. Oregon’s timber harvest peaked in 1952 at 9.8 billion board feet. Since the interventions of environmental activists in the 1990s, harvests have diminished significantly. Between 2017 and 2021, the state average was 3.8 billion board feet, according to the Oregon Forest Resources Institute.

Decreased timber harvests created fierce—sometimes violent—political divisions between environmentalists and loggers. Oregon Public Broadcasting reported that a 1990 moratorium on federal timber sales closed sixty-seven mills in Oregon. More than 7,000 mill workers lost their jobs. President Clinton’s 1994 Northwest Forest Plan reopened Oregon forests for timber sales, but at a reduced volume—about one-third of the pre-1990 supply. Since it did not ubiquitously protect old-growth, environmentalists were as incensed as the timber industry.

Oregon’s timber harvest

over time, in board feet

↓

In December 2023, the Forest Service proposed an amendment to the 1994 plan, one that emphasizes the need to adapt our forests for a hotter, drier climate. This proposal casts doubt on a strategy known as fire exclusion. A practice once promoted by the Forest Service itself, fire exclusion involves completely dousing all wildfires, even low-intensity, natural fires that would have regularly cleared the small trees and brush that now endanger old-growth.

“More than a century of fire exclusion and other management practices have resulted in overly dense and homogenous forest conditions that heighten the risk of large, high- severity fires,” the new proposal argues. “Such management practices have resulted in forest composition and structure that is more vulnerable to fire because forests often have higher densities of smaller trees and shrubs and a lower proportion of fire-resilient species than were historically present.”

While there’s no perfect agreement between environmentalists and the timber industry, the dual failures of Forest Service policy—overharvesting national forests through timber sales and suppressing natural fire—have united small coalitions of environmentalists and timber officials.

In Oregon, John Shelk BA’67, managing director of Ochoco Lumber Co., has found common ground with environmental lawyer Susan Jane Brown, who needs Shelk to keep the mill open to process small trees felled to thin overly dense, fire-susceptible stands in the Malheur National Forest.

In Northern California and Southern Oregon, Galen Smith BA’06, who also works in the timber industry, devotes much of his time to restoring forests after high-mortality fires.

Ecologists like Eklund, and like Linnea Hardlund BA’13, who researches giant sequoias with Save the Redwoods League in Northern California, approach forest management from a different perspective, but often with similar goals: like timber executives, they work to bolster existing forests against wildfires of growing intensity.

↑ “We’re in this for the long term,” says Galen Smith BA’06 of Collins. “We want to make sure there’s still forest land to manage in the future.”

For Willamette professors like David Craig and Joe Bowersox, and for their former students, including Liam Chambers BA’21, part of the job is imagining new responses to projected climate futures, such as reseeding forests with trees that will resist a warmer, drier climate better than their native counterparts.

These days, many conservationists and timber representatives agree that some trees have got to go. The sticking point is which ones, where, and how many. For environmentalists, old-growth is irreplaceable. Timber executives argue that lumber is a significant source of income for workers in the Pacific Northwest, that there’s a housing shortage in the United States, and that demand for building supplies has surged since the pandemic. Most people on both sides agree that high-intensity wildfire endangers old-growth trees, timber values, and communities in the wildland-urban interface—places such as Detroit, Oregon, which was leveled by the 2020 Santiam Fire. Most also agree that such a complex problem demands cooperation between conservationists and timber industry representatives to protect what’s left of US forests and prepare them for a hotter future.

W

While Eklund was collecting data in the forest in 2021, Smith was watching 50,000 acres of company-managed land burn in the high-severity Dixie and Cougar Peak fires. Smith is vice president of resources for Collins—the first US lumber company to earn certification from the Forest Stewardship Council, which requires forest managers to “expand protection of water quality, prohibit harvest of rare old-growth forest, prevent loss of natural forest cover, and prohibit highly hazardous chemicals.”

After high-mortality, wind-driven crown fires, what’s left is “a moonscape,” Smith says. “The only thing that will really come back without intervention is brush and grass. It will cease to be a forest.” At Collins, replanting involves clearing brush and dead vegetation to promote exposure for sun-tolerant species like ponderosa pine. It involves the use of herbicides to reduce sun, water, and nutrient competition between vulnerable saplings and other vegetation. Once a canopy is reestablished, the forest becomes more capable of self-regulation.

↑ The Lookout Fire severely

damaged Oregon’s H.J. Andrews

Experimental Forest.

These practices sounded similar to those used by Hardlund and Save the Redwoods, so I asked her to weigh in. “People don’t want to think about doing site preparation to replant trees,” Hardlund said. “People don’t want to think about reducing forest density. But we’ve put ourselves into a position by suppressing fire for so long that those are the tools that we have to use to get back on track ecologically. We need to re-establish forest cover after these high severity wildfires.”

My conversation with Smith revolved around the idea of restoring forests to their historic conditions. Before the twentieth century, Smith told me, forests contained “multi-age classes; there’d be some big trees, there’d be some saplings, some in between. Occasionally there’d be some disturbance like a fire, and the forest would somewhat self-manage. Certain Indigenous groups would do some elements of prescribed fire. There would be lightning strikes. The forest would self-manage the density that it could support.”

I asked Smith to describe how it felt to return to the forest in Chester, California, after the Dixie Fire. “I mean, it kind of just takes your breath away,” he said. “I grew up going to some of these forests a couple times a year. My uncle and his sons lived in Chester. He still does. So it’s a sense of grief, I would say, for what’s been lost. And I think there’s also a sense of hope that we’re actively coming back from it, that we’re replanting, that it’s going to be a forest again. We’re in this for the long term. We want to make sure there’s still forest land there to manage in the future.”

Because of ineffective forest management, including the total suppression of natural fire, what we’re left with today, Smith says, are forests that cannot support their own tree density. Lack of sunlight, water, and nutrients, accelerated by climate change, result in excess vulnerability to catastrophic fires.

The story of the US government’s forest management regime begins in 1910, when a wildfire known as the Big Blowup razed three million acres in northern Idaho and western Montana over just two days. Still the largest fire in US history, it killed more than eighty people and reduced small towns to heaps of ash. Wallace, Idaho, was leveled except for a few shells of blackened brick.

The Big Blowup threatened the credibility of the US Forest Service as an agency tasked with managing the ecological and economic health of US forestlands. Five years earlier, Gifford Pinchot had become the inaugural head of the agency. Under his direction, the Forest Service had solidified a practice of total wildfire suppression. This contradicted another main theory of forest management—which advocated for “light burning,” or small fires, natural or prescribed, that clear dry brush on the forest floor without damaging large, old-growth trees.

Total wildfire suppression had folk logic on its side: why set fire to a forest you aim to protect? After the Big Blowup, suppression advocates argued that light burning was “a deliberate continuation of the destructive surface fires which were steadily and irresistibly eating up the pine forests of our western states,” as William B. Greeley, third chief of the Forest Service, put it in 1920.

The debate between suppression and burning culminated in the 1935 “10 a.m. Policy,” which dictated that any fire reported overnight should be contained by the following morning. Legions of young men enlisted in the Civilian Conservation Corps for work to improve national parks and public lands, fighting fires as part of the job. Housed in military-style encampments with barracks and mess halls, the men were offered job security during the Great Depression in exchange for going to war with wildfire.

As Phillip Connors observes in his 2020 New York Times article on the history of fire suppression, firefighting units even adopted the military tactics of paratroopers. The Forest Service emphasized the parallel with its 1944 Smokey Bear ad campaign. In the famous poster, Smokey points directly at the viewer, looming over the words “Only You” in bold—a callback to the 1917 Uncle Sam Army recruitment flyer.

The 10 a.m. Policy persisted until the late 1970s. That’s when a preponderance of research emerged to substantiate the benefits of light burning, and the US Forest Service switched to prescribed burns. But a half century of suppression had produced enormous quantities of dry fuel in unburned forests, making fires more difficult than ever to control. When the natural-burning Yellowstone Fire of 1988 scorched a million acres of the national park and its surroundings, public opinion swayed, again, in favor of extinguishing wildfires as quickly and completely as possible. Though scientists largely agreed about the benefits of mild fires, forest conditions were not conducive to low-intensity fires without reducing stand density. Foresters are making progress, but even today, prescribed burns are not yet ubiquitous.

A

A difficult question remains: how do forest managers and ecologists ensure the future health of a forest that must withstand historically unprecedented heat, drought, and extreme weather?

“There’s no historical precedent for what we’re seeing,” Hardlund says of her work with Save the Redwoods. “We’re doing adaptive management, which is just you try something and see if it works, and if it doesn’t work, then you adapt and you fix it and you do something different.”

Some ecologists, including Willamette Professor of Biology David Craig, have experimented with replanting forests with non-native trees already adapted to regional climate projections, a practice known as assisted migration. Of historic replanting regimes, Craig said, “None of it is good enough for the climate forecast of forty to sixty years ahead. We’ve got to look at all the best climate models of the Willamette Valley: our holdings are going to look like the Sacramento Valley.” This means the existing forest composition in Western Oregon—for example, dense stands of Douglas fir—may not be able to withstand tomorrow’s wildfires.

Joe Bowersox, professor of environmental science at Willamette, noticed a surge of student interest in sustainable forestry around the early 2010s. With Professor Emerita of Environmental Science Karen Arabas and Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Ruth Feingold, he negotiated with Oregon State University to expand Willamette’s 3+2 Forestry program, in which students enroll in a master of forestry at OSU after completing a bachelor’s at Willamette. Bowersox says this uptick in interest seemed to coincide with Willamette’s 2008 acquisition of forest land at Zena, where students can experiment hands-on with tree cultivation, biogeography, and ecological forestry.

Examples of tree species

that can be fire-resistant

↓

The topography and diverse composition of Willamette at Zena make it an exceptional resource for instruction in ecology and forest management. The 305-acre forest, located just west of Salem, contains stands of Douglas fir, Oregon white oak, bigleaf maple, ponderosa pines, and riparian ash galleries, all at varying levels of maturity. Some of its slopes are wet, shady, and north-facing, while south-facing slopes are dry and sunny. The range of forest conditions allows students to work on invasive species removal, density management, carbon-uptake monitoring, and seedling regeneration—skills that Hardlund and Smith use in their work today.

Bowersox said students have also worked on evaluating “ecosystem services,” balancing the forest’s habitat value and its economic value as a harvestable plot. (A recent gift from Shelk and his wife, Linda, is helping to fund an indoor/outdoor classroom at Willamette at Zena. The John BA’67 and Linda Shelk Educational Pavilion will serve students from all disciplines.)

During my conversations with foresters and ecologists, I was searching for answers about best forestry practices. I consider myself environmentally minded, and I wanted to know: what’s best for the longevity of our forests? When I asked Bowersox about ideal forest management, he reminded me of the issue’s complexity.

“There are many ideals,” he said. It depends on your objectives, the forest’s species composition, and the site conditions. It depends on the slope, the aspect, and the soil’s moisture content. If you’re trying to encourage natural regeneration, it might be necessary to cut down large trees to increase sun exposure for seedlings. Previous owners of the Willamette property at Zena planted ponderosa pine at about 450 to 500 trees per acre. To account for fuel build-up, Bowersox said, “We should probably take that down to between 150 and 180 trees per acre.” On the other hand, he told me, trees near rivers and streams shouldn’t be thinned at all.

To improve wildfire resilience, Willamette at Zena is undergoing a series of experiments. Two large, prescribed burns have reduced understory growth. In a recent timber harvest, Bowersox, students, and other faculty left oaks and maples to provide shade. They also left downed, woody debris to maintain the soil’s moisture content. And instead of replanting the stand with its original species composition—ninety percent Douglas fir and ten percent mixed hardwood—they replanted with thirty-five percent to forty percent Douglas fir and thirty-five percent to forty percent Willamette Valley ponderosa pine, with incense cedar, coast redwood, and grand fir for the remainder. It’s a lesson in adaptation: to survive a changing climate, the forest itself must change.

New forestry demands that land managers look simultaneously to the past and to the future. Our forests must be able to withstand megafires, drought, high winds, and periods of heavy precipitation. If we hope to continue using wood products, forests must continue to yield sustainable timber harvests. Decades of fire suppression, a kind of overcompensation intended to protect timber values and communities in the wildland-urban interface, produced vulnerable, high-mortality forests.

Now, we have to compensate again. Today, however, with difficult work ahead of us, we seem unlikely to overreact. Contemporary US forests require even more research and active management to maintain their longevity and health. Tomorrow’s forests will not—and cannot—look the same as yesterday’s. The climate equation, in which the ecological future is merely a remainder of the past, is something like the equation for hope: hope for what can be salvaged, rebuilt, and reimagined, minus grief, for what can’t.

Into the Woods

Environmentalists and timber officials approach forest management from different perspectives, but often with similar goals.

Tracking bear cubs, barred owls, and pika in the Andrews Forest

To recover economic losses after a wildfire, windstorm, or insect infestation, timber companies sometimes practice “salvage logging,” assessing trees for cracks, fungal stain, and rot before extracting logs that can be milled for lumber. But some fallen trees serve a different purpose.

Looking for her niche in environmental conservation, Alyssa Eklund BA’21 took an interest in woody debris in western Oregon’s H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest. These complexes of fallen logs, branches, roots, and sediment are known as “large wood”—natural structures you might use as a bridge to cross a forest creek.

Eklund’s research for her master’s in fisheries and wildlife administration at Oregon State identified wildlife interactions with large wood along Lookout Creek in the Andrews Forest. She placed motion-sensing cameras to record videos of animal activity at large wood sites. While previous research at Andrews Forest had focused on individual species or the impact of large wood on water flow, few studies had explored how wildlife interacts with deadfall complexes writ large.

Eklund anticipated certain behaviors caught on camera, such as the black bear lumbering across a log with a cub in tow. Others surprised her, such as the barred owl fishing a salamander from the creek with its talons, then perching on the roots of a stump to pull it apart.

Every study is going to

be a pre-fire study.

She was also surprised to see pika—which are known to inhabit rocky, high-altitude mountain environments without much vegetation—using the large wood. For Eklund, their appearance raises two questions: “Have they always been here, and we just haven’t been looking for them? Or is this more recent—like, what’s going on with the pika, and what are they doing down by the stream?”

Two years after she finished collecting data, a lightning strike ignited a wildfire that burned more than sixty-five percent of the Andrews Forest in 2023. In forests that grow hotter and drier each year, “every study is going to be a pre-fire study,” Eklund says now. “It’s pretty much a given that, eventually, it will burn from a wildfire.”

Future research may focus on the effectiveness of post-fire restoration efforts, which could include rebuilding large wood structures lost in the fire. These efforts, Eklund says, are understudied and require deeper analysis.

↑ Liam Chambers BA’21

Slowing the progress of wildfires and reducing their risk

In 2023, Liam Chambers BA’21 worked as a wildland firefighter and as a crew member

of the Community Wildfire Protection Corps. A subsidiary of AmeriCorps, CWPC aimed to improve the fire resilience of homes in Lane County, Oregon, the epicenter of the 173,000-acre Holiday Farm Fire in 2020. Chambers and his crew went door to door, speaking to residents about wildfire risk reduction. If homeowners expressed interest, the crew would clear ignition zones around the structure for free, Chambers says, “thinning trees to be about eighteen feet apart.” To reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire, the crew also removed “laddering fuels”—low-lying brush capable of carrying fire into a tree’s canopy.

CWPC’s practices look much the same as the tactics Chambers and his fellow firefighters used to contain the wildfire near Roseburg, Oregon, in September 2023. First, the crew removed all burnable material from a strip of land at the fire’s edge. Then, they cleared a thirty-foot contingency line half a mile from the fires, removing laddering fuels that endangered old-growth cedars and Douglas fir. To offer further protection, the crew gave large trees a “haircut,” trimming their branches.

We’re not fighting

something inherently evil.

The title “firefighter” suggests an adversarial role, but, as Chambers observes, fires can be healthy for an ecosystem. He describes the “beauty or ecological functionality of a fire that was not so much fought and put out but facilitated and mitigated by a containment line. There’s a danger in fire, but . . . we’re not fighting something inherently evil.”

Today’s wildland firefighters imitate the ecological role of natural, low-temperature fires that regulated fuel loads in forests before timber overharvesting and urbanization. With the expansion of urban, suburban, and exurban zones throughout the western US, many communities now lie in the wildland-urban interface, where built environments commingle with natural ones.

The prospect that the healthiest approach to fire management is to let it burn can be “pretty despairing and scary news for communities when there’s an active fire,” Chambers says. “I’ve even heard instances of suspicion of the wildland firefighting industry when a containment line isn’t immediately built or there’s not an immediate initial attack.” Communities like Lane County carry a collective trauma after megafires. To suggest prescribed burns in their area seems to many like a cruel irony—though it may be the most effective solution for mitigating high-severity wildfires in the future.

Cutting down some trees to save the others

John Shelk BA’67, managing director of Ochoco Lumber Co. in Prineville, Oregon, is a leading voice in the collaborative efforts between environmentalists and timber industry leaders in the Pacific Northwest. A firsthand witness to the timber wars of the 1990s, Shelk guided Ochoco through the industry’s economic collapse from Idaho to the Cascades.

In the late 1980s, environmentalists were galvanized against the decimation of old-growth forests. West of the Cascades, clearcutting a specified area of a forest was relatively common at the time, and was sanctioned by the US Forest Service, which sold timber from public lands to the forest products industry. “The directive was to harvest all of the trees on that forty acres and then replant them,” Shelk recalls. “Environmentalists were concerned about clear-cutting and taking all the old-growth trees out and replacing them with small, second-growth trees.” This differs from the single-tree harvesting practices east of the Cascades, where ponderosa pines were marked for removal on an individual basis.

When the northern spotted owl was designated as “threatened” in 1990 under the Endangered Species Act, everything changed. As reported by Oregon Public Broadcasting, the evolutionary biologist Russell Lande showed that a landscape must comprise about one-quarter old-growth forest to sustain a population of spotted owls. No protections existed for the old-growth itself, but logging operations could be halted if they threatened an endangered species. Because of the northern spotted owl, the Forest Service halted timber harvesting across thirteen national forests in Washington and Oregon.

As a result, Shelk weathered a storm of sawmill closures across the Northwest. “We went from close to forty sawmills east of the Cascades in Oregon to maybe eight or ten sawmills,” he says. “We continued to reduce until at one point we had three or four sawmills east of the Cascades.” The downturn in logging towns was dramatic: more than 7,000 mill workers lost their jobs between 1990 and 1992. “About all that was left in the community was the retired contingent,” Shelk says, “plus the few people that then ran, say, the local hardware store or a gas station or grocery store. The economic devastation was much as you would expect from a town in West Virginia where the coal seams ran out.”

“You have a forest that

can withstand a fire.

Preserving the habitats of spotted owls incited a series of lawsuits, congressional hearings, and protests in which lobbyists pursued litigation against environmentalist groups to reverse the moratorium on logging in the Pacific Northwest. One of these arguments emphasized the role of loggers in responding to wildfires. In Shelk’s view, loggers were often the first to discover an outbreak of wildfire. “They would rush their equipment over to that fire and, with a combination of manpower plus larger mechanized equipment, put the fire out when it was in its very early stages,” Shelk says. When loggers left the forests in the 1990s, small fires “would escape that initial attack and . . . grow into multi-thousand-acrefires.”

Timber lobbyists saw an opportunity to leverage intensifying wildfires against environmentalist groups. “Someone had the idea to pin the blame on the environmental community who were restricting vegetative management activity on the national forests through their lawsuits,” Shelk says. “A group of smart, strategic-minded environmentalists thought, ‘Maybe we ought to engage with the forest industry and see if we can reenter the national forests in a less intrusive way than in the past.’” Among these environmentalists was Susan Jane Brown, who agreed there was a need for forest management, which would remove small saplings and second-growth trees, to prevent catastrophic wildfires from wiping out old growth.

Shelk has collaborated with Brown and environmentalist organizations, despite the reproach of other timber executives. Shelk has called himself a pariah—during one forest meeting, he was accused of “sleeping with the enemy.” But he’s found productive experimental uses for sawmill waste and small trees that have helped him keep mills open in towns like John Day, Oregon. “We have hosted a plant on our mill site that was owned by a branch of the US Forest Endowment, which is a national nonprofit to render waste from the forest into charcoal that then can be made into energy briquettes, soil additives and amendments, and filter products,” Shelk says. Ochoco also makes other products from sawmill byproducts, including shavings for animal bedding and wood chips for manufacturing paper.

That doesn’t mean Ochoco has ceased producing two-by-fours. “There has to be an active management component that essentially spaces trees out in a forest, gives them maybe fifteen, eighteen, twenty feet between trees so they’re able to get sufficient moisture, nutrients, and sunlight,” Shelk says. This means cutting down larger trees in densely wooded forests and using prescribed fire to clear brush. “After you’ve done this thinning, you have a forest that can withstand a forest fire.”

For preservationists, this might seem like a compromise—some sizable trees are still being cut down. However, considering the Forest Service’s years of fire suppression, appropriate thinning in overly dense, dry-zone forests could improve their fire resilience and better resemble what our forests would have looked like if natural fires had been allowed to burn.

Investing in green, thriving forests

When Galen Smith BA’06 was growing up, he and his family would visit the Almanor Forest near Chester, California, to check on the forest management activities of Collins, his family’s Oregon-based timber company. Continuing his family’s eighty-year legacy of forest management near Chester and Lakeview, Oregon, Smith has worked with Collins’s forestry team in the Almanor, as a production supervisor in a Collins sawmill, and now as the company’s vice president of resources.

Smith and his family toured the Almanor twice a year—once in winter, when the forest was blanketed with snow, and once in summer for the annual company picnic. He remembers the smell of milled pine, the heat of dry kilns, and the crash when a logger felled a tree. Each morning, he and his siblings would walk down to the gas station for a newspaper and powdered donuts. They’d stop by the local arts and crafts fair and, after dinner, feed fish in the pond behind the Black Forest Lodge. “It was all part of our first lesson about the three-legged stool of community, environment, and economy,” Smith says.

I was exactly where I needed to be.

Though Smith spent time in other jobs, he felt called back to Collins to manage the forests. Working for the family company isn’t always easy—the personal and professional are inseparable. But after fires in 2021 scorched thousands of acres of the Collins-managed Almanor and Lakeview forests, Smith felt a renewed sense of purpose in his role. “I had this strong feeling that I was exactly where I was supposed to be,” he says. “Now I get to help make sure the acres that burned return to green forestland.”

Perhaps the greatest challenge Smith and the company face is improving the fire-resilience of its forests. One of Collins’s responses to increased fire danger is altering the tree composition of a given stand. After years of fire suppression, white fir has proliferated in Collins’s forests. White fir is less drought-tolerant and needs more shade than ponderosa pine. Sometimes, Smith says, it’s appropriate to remove white fir and replant ponderosa to achieve a more historically representative species mix.

No forest is an island. “One of the biggest risks is how our neighbors manage their land,” Smith says. “In the case of catastrophic fire, a poorly managed stand next to us is probably a bigger risk than any spot on our land.” Ultimately, Smith emphasizes the importance of viewing forest health from a collaborative standpoint: “I don’t think anyone wants to see forest land with broad swaths of mortality from insects or drought impact or massive fire scars. We’re all invested in having these be green, thriving forests.

↑ Linnea Hardlund BA’13

Replanting where sequoias don’t return on their own

Linnea Hardlund BA’13 is a forest ecologist for the California nonprofit Save the Redwoods League and a graduate of UC Berkeley’s master of forestry program. Hardlund, whose research focuses on giant sequoias, witnessed the consequences of a hotter, drier climate and more than a century of fire suppression after the high-intensity Castle Fire burned more than 175,000 acres of California’s Alder Creek Grove in 2020. The Castle Fire killed an estimated ten percent to fourteen percent of giant sequoias in the Sierra Nevada, the tree’s only natural habitat. In 2021, the Windy Fire and King National Park Complex Fire are estimated to have killed another three percent to five percent. In two years, high-intensity wildfires decimated thirteen percent to nineteen percent of the global population of giant sequoias—some of Earth’s oldest and most massive trees.

Many of them hadn’t burned

in a hundred years.

Hardlund’s research on giant sequoia mortality corroborates the need for management regimes that prioritize reducing fuel loads and forest density. Reinstating prescribed fire—fires started intentionally by firefighters to burn off a buildup of undergrowth and ground fuels—is the ultimate goal.

“We’re trying to reduce tree density and fuel loads so that we can reintroduce healthy fire into those groves,” Hardlund says. “They just burned in 2020 and 2021, but before that, many of them hadn’t burned in over a hundred years.”

Though giant sequoias evolved to tolerate fire, the high winds and dry conditions sustained during the Castle Fire ignited the sequoia’s crowns, often more than 100 feet off the ground. Sequoias need some wildfire to coax open their semi-serotinous cones and clear understory competition for sunlight, but high-severity fires decimate large swathes of mature trees and their seed bank.

While Hardlund and her team have observed some regeneration following recent wildfires in giant sequoia groves, if seedlings in large, high-severity patches do not survive, no natural seed source remains, putting those groves under threat of contracting. Hardlund and Save the Redwoods League have begun replanting in high-mortality burn zones to establish seedlings in areas where sequoias were not returning on their own at high enough densities.

••

Chris Ketchum BA’15 is a poet and writer from Moscow, Idaho. He is a PhD candidate in creative writing at Georgia State University.