T

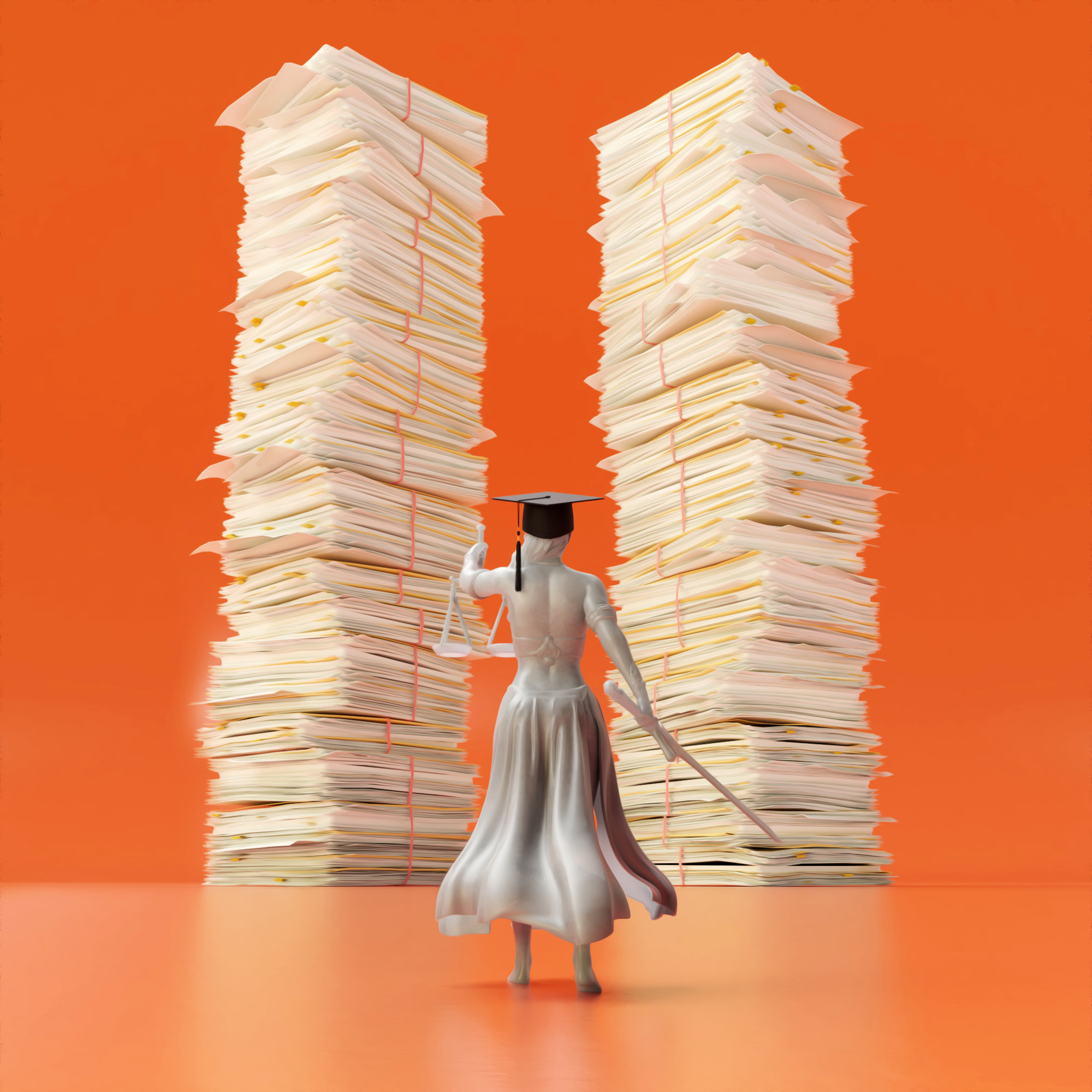

The big thump. It’s how new public defenders describe their first day on the job, when they’re greeted by a thick stack of cases on their desks. And it’s among the reasons there are such high levels of burnout and turnover among new lawyers who pursue a career defending people who cannot afford a private attorney.

“The practical reality is most public defenders will probably quit within the first few years of their practice. It’s really hard work,” says Kurt Wohlers, assistant professor of clinical law. He is in charge of Willamette Law’s new Criminal Defense Clinic, a for-credit practical skills clinic that pairs law school students with people who need defense lawyers.

Oregon lawmakers authorized short-term funding for three such clinics at the state’s law schools to help address the state’s public defense crisis, part of a plan to overhaul the state’s public defense system. Each month in Oregon, thousands of criminal defendants go without defense lawyers, violating their state and federal constitutional rights.

More than 90 percent of people charged with crimes in Oregon rely on public defenders to represent them, according to a state report. And a 2022 report by the American Bar Association shows the state had only 31 percent of the public defense attorneys it needed to handle caseloads. Similar studies found that public defenders in Oregon were taking on too many cases, threatening their ability to provide adequate representation to their clients and leaving people in jail without legal representation. Despite the cash infusion from the state legislature, more than 4,000 people lacked a lawyer in February 2025.

Willamette’s new clinic aims to address some of the systemic issues, Wohlers says, even as it fulfills the law school’s mission to provide practical, real-world experience to its students before they graduate. The clinic puts second- and third-year law students to work defending people facing misdemeanor charges in Marion County. The hope is that the clinic will not only prepare graduates for careers in public defense but also ease the burden on the state’s strained indigent defense system.

“The practical reality is most public defenders will probably quit within the first few years of their practice. It’s really hard work.”

The clinic fulfills the loftier mission, too, of carrying out the U.S. court system’s constitutional promise to those accused of crimes. Anyone facing criminal charges who cannot afford a lawyer has a right to an adequate attorney at government expense. It’s a right established in the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 Gideon v. Wainwright decision.

In the long run, the clinics at Willamette and the state’s other law schools are building a feeder system for new lawyers to become public defenders, says Brook Reinhard JD’09, former executive director at Public Defender Services of Lane County and now a lawyer in private practice. Reinhard took part in a different clinic during his years at Willamette, and he says it offered practical, supervised legal experience that was pivotal in his growth as a new lawyer.

“Law school doesn’t actually teach how to be a lawyer; it teaches you how to think like a lawyer,” Reinhard says. “And so the vital part about a clinic is it actually teaches you real-world skills in being a lawyer.”

In addition to the law school clinics, the Oregon Public Defense Commission has boosted the number of public defenders on its payroll; until recently, almost all public defense work was done by individual lawyers or nonprofit agencies and consortiums of private defense attorneys. Twenty such public defenders have joined the Oregon Public Defense Commission since 2023, says Aaron Jeffers JD’11, chief deputy defender for the agency and a board member of Legal Aid Services of Oregon. The governor’s budget calls for the Oregon Public Defense Commission to hire an additional forty public defenders.

W

Willamette Law’s criminal defense clinic attracts a mix of students, including those who know they want to be public defenders and those who haven’t yet chosen a post-graduation path. During class, students review their assigned cases; they’re partnered up so that two students represent one client. They learn how to review evidence and discovery, including police reports and body camera footage. Then, they interview clients and prepare a defense. Wohlers attends client meetings and any court appearances and helps students prepare defense and trial strategies. In general, though, students take the lead.

They also spend class time discussing how to avoid burnout and how to manage secondary trauma caused by the constant exposure to traumatic events experienced by their clients. No class can fully prepare students for the whirlwind pace of a public defense job, but the clinic offers a glimpse, Wohlers says.

“There are a lot of times where you’re rushing around between courtrooms and you’re filling out documents in one courtroom and running over to the other,” he says. “And you don’t get that perspective when you’re in law school, but you really get to see it when you’re in court every single day.”

Wohlers says that many students enter the clinic “a little bit scared to walk up there in front of a judge and a courtroom filled with people.” But by the end of the semester, their courtroom confidence blooms.

“Getting to see how the students develop is really, really rewarding,” Wohlers says. “The confidence level is something that you cannot teach in a law school course. You just have to do it multiple times.”

Occasionally, clients worry that their defense might suffer because they’re represented by students. But they’re often getting superior representation for misdemeanor cases, Wohlers says, because there are two law students for each defendant, both supervised by an experienced public defender.

“And,” he says, “you also get two students who are really excited to represent you.”

••

Erika Bolstad is a journalist and author in Portland who writes frequently for Stateline, a national news nonprofit that covers state policy matters.