L.A. Paul, a philosopher who studies decision theory, explores the problem of making choices after a life-altering event in her book Transformative Experience. Two types of transformative experiences exist in Paul’s formulation—epistemic and personal transformations. The first describes experiences in which we acquire new, often sensory knowledge, like when we taste a new food for the first time. Personal transformations describe experiences forceful enough to alter us entirely, even our system of values, like the birth of a child or a religious conversion.

After speaking to six Willamette alumni who have changed tack in their professional careers, I wondered about a slight variation on Paul’s personal transformations. What about those experiences in our lives that bring a latent value to the fore?

In the profiles that follow, an advocate for carceral justice decamps to Spain. Two former legislative aides find niches in caregiving—one medical, one spiritual. A comedian empowers his community to grow their own food. A manager discovers her passion for enabling leaders to do their best work, and a Hollywood screenwriter applies his experience to teaching English. Though their work varies, they are united by a commitment to others. After all, “Not unto ourselves alone are we born.”

You Can’t Eat Jokes

Nathan Brannon BA’06

Comedian → Gardener

↑ Photograph by Patrick Record

Nathan Brannon performed a stand-up set at the Burbank Comedy Festival in California in 2018. He had just bought a house in Walla Walla, Washington, “the smallest town I’ve ever lived in by at least 100,000 people,” he told the audience. “I said a phrase this past year that I’ve never said before in my entire life; I said, ‘Damn it, the neighbor’s alpaca has gotten into our yard again.’”

Brannon got his start in stand-up at Willamette and went on the road after graduation. The accolades stacked up. He produced two comedy albums, toured with Dave Chappelle, and earned the title of Portland’s Funniest Person.

But when COVID shuttered comedy clubs around the country, Brannon lost his primary source of income. “My kid was one and a half, and you’re sitting there kind of, ‘What do I do? I can’t make anybody laugh right now.’”

Since the early 2010s, Brannon had also been a hydroponic and aquaponic gardener. He figured he could contribute to household expenses by growing healthy food. The more he grew, the more he realized there were “other parents out there in the exact same boat.” Brannon started a social media campaign, “Dig It with Nathan,” to take “the stigma and mystery” out of gardening.

“When you look at this plant, when you walk outside and you see it growing, I hope it reminds you that you have something of value.”

Today, Brannon is an education manager for the Sustainable Living Center’s Farm to School program in Walla Walla. In this role, he runs the gardening program at a local school—the poorest in the district, Brannon says. He also works with incarcerated youth to build hydroponics systems: The teens learn to harvest spices and start fruit trees. “When they’re released,” he says, “they can enjoy the fruit of that tree with their families.”

Brannon gives talks about gardening, too. He especially likes to introduce young gardeners to George Washington Carver. Born into slavery, Carver rose to prominence after the Civil War as the agricultural scientist who urged Southern farmers to plant nitrogen-fixers like peanuts and soybeans to restore soil depleted by cotton monocropping. Brannon tells his young audiences that Carver “was written off by the same farms he ended up saving later on,” and he shares this message: “The idea is that you have a talent; you probably don’t even know you have it yet.” Then he hands out legume seeds and says, “When you look at this plant, when you walk outside and you see it growing, I hope it reminds you that you have something of value.”

As it turns out, teaching people to grow food is not so different from comedy. “With standup,” he says, “it’s not enough to think of good ideas or express your experiences, if you can’t figure out how to find the spots in an audience’s experience where they overlap.” He connects with families by sharing the story of economic distress he and his family felt during the pandemic. In a community where many have experienced food insecurity, they know exactly what he means.

Cultural Exchange

Jordan Schott BA’21

U.S. Senate staffer → teacher in Spain

When Jordan Schott graduated from Willamette, she went into government—to continue a project she’d started as a politics, policy, law, and ethics major.

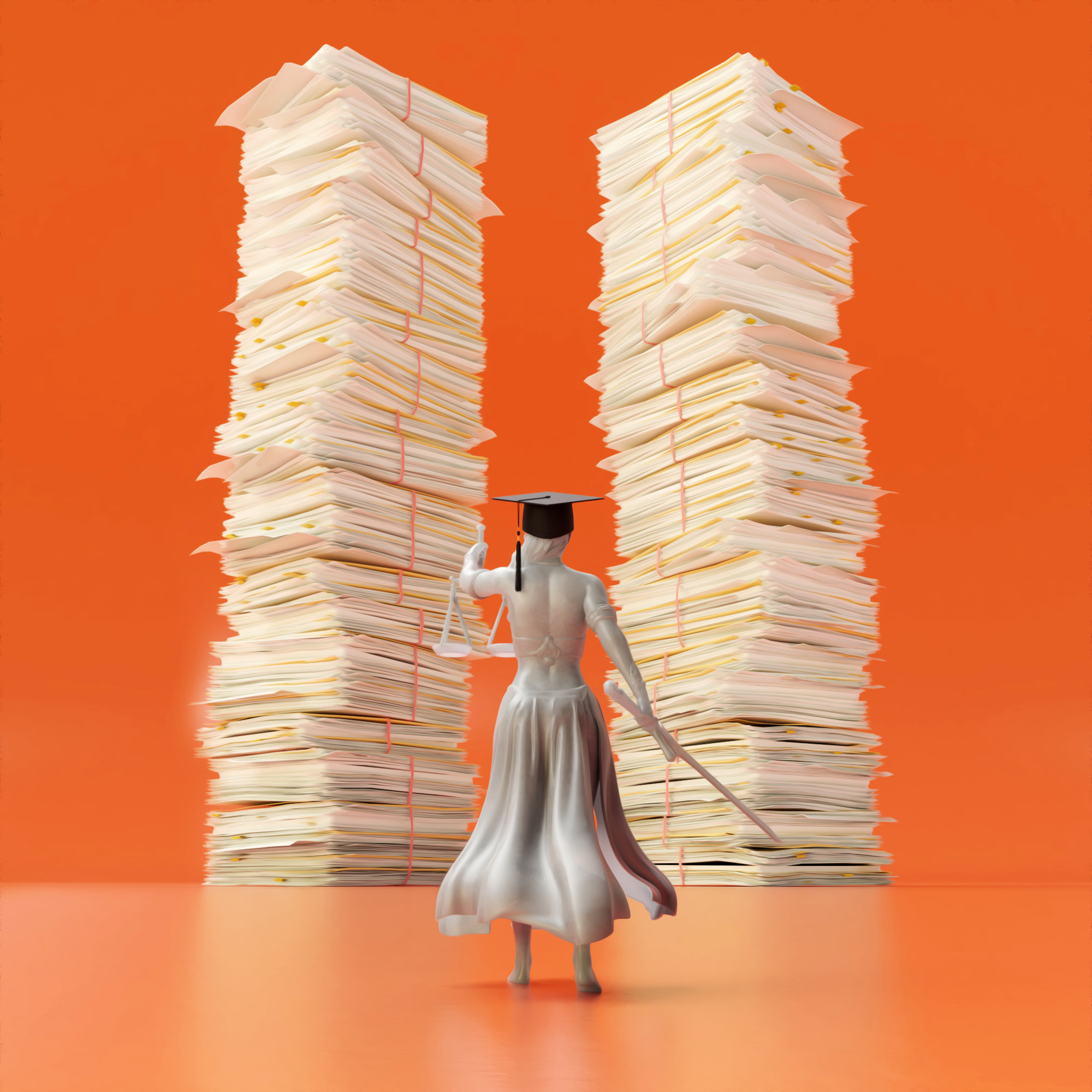

In Professor Melissa Buis’s “Restorative Justice” course, which enrolls a mix of Willamette students and inmates of the Oregon State Penitentiary, Schott initiated an effort to amend the Oregon constitution. Together with Niki Kates BA’20, Riley Burton BA’20, and members of the penitentiary’s Black cultural club, she formed Oregonians Against Slavery and Involuntary Servitude. Their goal was to remove the constitution’s slavery exception clause, which permitted compulsory and uncompensated labor in Oregon prisons. After years of work, their efforts paid off on Election Day in 2022, when Oregonians voted to remove the slavery exception from the state constitution.

That project landed Scott a position on U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley’s legislative team. She moved to Washington, D.C., to become a legislative aide in Merkley’s office, where she hoped to achieve the same reform on the federal level. But after the 2024 elections, she knew the timing wasn’t right for federal reform.

So, Schott moved to a small town near Valencia, Spain, to teach English in public schools. Sometimes, local teachers ask her to prepare presentations about life in the U.S. And every day, the cultural exchange teaches her something, too, including about government programs in a place far removed from D.C. When the time comes for her next pivot, she’s sure to bring this experience with her.

Comfort at the End of Life

Blayne Higa BA’97

Legislative aide → Buddhist minister

↑ Photograph by Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu

Blayne Higa was working as a senior legislative aide in the Hawaii House of Representatives when he received word from his mother that her longtime partner was nearing the end of his life.

Higa flew from Honolulu to his hometown of Hilo, Hawaii, to be with them. This was in 2010, and Higa, who was raised Buddhist, was at the time serving as a layperson at his local temple. As Higa watched his mother care for her ailing partner, he felt called to care for others in a similar way. For the first time, he began to seriously consider the ministry.

“Life is unpredictable, impermanent, and short,” Higa says. “I didn’t want to look back and say I didn’t venture down this path and fully explore it.”

He pursued ordination, a multiyear process that involved traveling to Kyoto, Japan, to spend time at the head temple of the Hongwanji-ha tradition of Jōdo Shinshū. Back in Hawaii, he became a part-time minister while working full time at a nonprofit. Then his family asked Higa to perform the end-of-life service for his 100-year-old grandmother.

“To do that for her was challenging and difficult—but also the most meaningful thing I’ve done,” Higa says. “After that experience, I knew what I needed to do.”

Higa quit his job. He enrolled at the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley, California, where he earned a master of divinity degree. He then received additional certification in Japan.

“Life is unpredictable, impermanent, and short. I didn’t want to look back and say I didn’t venture down this path and fully explore it.”

Today, Higa is resident minister of the Kona Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, a Shin Buddhist temple on Hawaii’s Big Island. He spends his days consulting with community members on questions of faith and listening to their concerns. The temple also functions as a community center, including as a place of respite for the unhoused.

Higa especially values the chance to work with families at the end of life—a sacred transition, he calls it. “Old age, sickness, and death are eternal truths that the Buddha taught,” he says. “The role of a spiritual caregiver is to listen with compassion and attentiveness, to be present with suffering in all forms.”

Life in the ER

John Turner BA’04

Public policy → Emergency physician

Before he became a doctor, John Turner worked for one. Oregon State Sen. Alan Bates was a family physician in Southern Oregon for twenty-five years before he joined the legislature, where he operated an ad hoc medical clinic for staff and legislators in the State Capitol.

“He had a pager and a black doctor’s bag, which would be up in our office,” Turner recalls. Together, Turner and Bates would respond to minor injuries or health emergencies, like, once, a fall down the stairs. “We’d be the first responders before the first responders would show up. Being there to take care of somebody really had an impact on me.”

Turner considers his greatest policy achievement to be his work to expand insurance coverage to low-income Oregonians through the state’s Medicaid program. House Bills 2009 and 2116 passed in June 2009, resulting in health coverage for 95 percent of Oregon children.

But “there was part of me that always wanted to be a doctor,” Turner says. In 2009, he left the Capitol to pursue that dream, and eventually, he earned an MD at Oregon Health and Science University.

Today, Turner is an emergency physician in the Willamette Valley and a medical director for EMS agencies in Clackamas County. “I love emergency medicine because I never know what I’m going to get,” he says. He might treat cardiac arrest in one patient and a mental health crisis in the next.

Turner also trains EMS responders to provide treatment for patients with substance- and opioid-use disorder. As Turner explains, people who have experienced a non-fatal overdose are at the highest risk of fatality for the next forty-eight hours. He is part of a project that aims to prevent this by treating withdrawal symptoms and protecting against future overdose.

He still has a foot in the door in politics, serving on the executive committee of the Oregon Medical Association and working with the Oregon College of Emergency Physicians. It’s important for doctors to maintain a relationship with Oregon legislators, because, he says, “if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.”

Helping Leaders Shine

Stacy West BA’06, MBA’12

Executive director → Executive assistant

↑ Photograph by Joanna Kulesza

Stacy West began her career as a study abroad advisor at Willamette. She went on to serve as executive director of the Oregon Symphony Association in Salem and, later, as a recruiter for a study abroad company. There, she also developed and marketed a Spanish language program for professionals.

But with two young children, that work no longer felt like the right fit. “You’re going through a life shift,” she recalls. “I wanted to find a job that would allow me flexibility.”

Through a series of professional connections, she became an executive assistant at the New Orleans-based incubator Camelback Ventures, where she tapped into communication skills she’d honed in international education.

West loved being able to free up Camelback founder Aaron Walker to “go be a leader,” she says. And she wasn’t the only one who saw the impact of her role. In fact, Walker’s wife, Ify, wrote a post about West that went viral on social media. It described not only how West enabled Walker to manage his company but also how she purchased books for the Walkers’ young children, set aside blocks in Walker’s calendar for date nights, and answered emails on Walker’s behalf—even those sent by Ify herself. “She was privy to all the inner workings of our life,” Ify wrote. “Trusted without reservation.”

West calls Ify’s public expression of gratitude “one of the most touching moments of my career.”

Today, West has moved on from Camelback to work as a contractor in executive support and as a consultant in organizational operations. She manages her clients’ calendars and travel, coordinates events, and helps them prioritize their projects. Her work in organizational operations entails more systems-based work, such as building project-management structures, writing standard operating procedures, and restructuring clients’ email inboxes to manage large volumes of correspondence.

For West, the joy arises from solving the puzzle of a client’s competing responsibilities. In doing so, she can “free them up to do their superpower.”

Lights, Camera, Classroom

Michael Ross BA’04

TV writer → English teacher

Just after Michael Ross’s camera flickered on for our Zoom interview, something behind his screen caught his eye. He saw one of his students outside the classroom door, nose to the window. A teacher’s half-smile—somewhere between sternness and affection—crossed Ross’s face.

Ross teaches English language arts at a South Los Angeles charter school, but it was the film industry that brought him to the city. As an MFA student in screenwriting at the University of Southern California, Ross presented a speculative script for Grey’s Anatomy to a literary manager for whom he was interning—and earned representation. He went on to write for a range of TV dramas (Switched at Birth, Firefly Lane, Relationship Status, Day of the Dead), working fulltime in TV for fifteen years.

Over time, he saw the industry change. Shows used to run for ten seasons. “And it started being the case that every show I got on was only one season. It’s hard to move up, and the work’s inconsistent.” In 2023, the Writers Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA strikes halted production across the industry. Ross’s husband, an educational consultant, suggested teaching. Ross liked the idea.

Now, Ross is a high school teacher in a school with a predominantly Latino population—a demographic largely excluded from the Western canon. He teaches a mix of literary classics and contemporary works by writers of color, and he approaches the classics from a modern lens. “With Frankenstein,” for example, “I’m trying to tie some of what we’re teaching to the AI debate: Are we creating something that we’re going to regret, or are we buying into something that we’re not going to see the consequences of?”

Ross also teaches a film-as-literature elective. In one unit, students learn to storyboard, shoot, and edit original short films. “We live in L.A.,” he says. “I want to teach these kids about jobs in the film industry that are not being a movie star.”

I asked Ross if he ever misses TV. “My job was literally sitting in a room with seven to ten other people making up stories all day,” he answered, and then smiled—no need for a teacher’s stoicism this time. “I love nothing more than when we get to do creative workshop days in here. As the kids start writing short scripts, I’m in my zone.”

••

Chris Ketchum BA’15 is a poet and writer from Moscow, Idaho.